INTRODUCTION

People do research for different purposes. Some do it in order to satisfy institutional requirements, some are keen to explore the link between theory and practice and use the findings to support/validate their instructional practices, while others may see themselves as responsible members of a research community and feel duty-bound to contribute to the development of new knowledge in their field of specialization.

Although their purposes may vary, they are ultimately interested to share their research with a wider group of people. They want to know if their work is read and cited by other people.

One simple way to find out whether your work reaches its intended audience is to look at your Google Scholar Citations. Google Scholar Citations provides information about the number of times your research papers have been read and cited by other scholars.

In academia, citations are often used as an indicator of research impact. The higher the citation number, the higher the impact of your research papers. Do note however that there are other indicators of research impact (see Nguyen & Renandya, 2020, for more information).

However a growing number of universities seem to attach greater importance to citation numbers these days. This is not surprising as international ranking organizations such as QS and Times Higher Education give research and publications a sizable weightage (up to 60%).

Let’s look at an example. We can see below that the article “Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Systemic-Functional perspectives” by Victor Lim has generated 205 citations. We can say that his paper is quite widely read and cited by other scholars.

If you click on the number of citation (right below ‘Cited by”), you will get detailed information who cited his paper, in which books or journals and in what year.

But not all published papers get good citation numbers. Some attract much fewer citations and others, none at all. My 2015 article “Extensive reading coursebooks in China” for example attracted only 10 citations (see below)!

This is despite the fact that this article was published in a Q1 journal (RELC Journal). The citation number may grow eventually, but at a very slow rate. I’d be lucky if the article received another 50 citations in the next 10 years. I can think of at least three reasons why the citation number is quite small:

- Within the broader field of L2 reading instruction, extensive reading is a fairly small topic.

- Coursebook is not a popular research topic either so the number of active researchers in this area is quite small.

- Extensive reading coursebooks are widely used in China but not in other countries. In Japan for example teachers use graded readers (not coursebooks) to promote the joy of reading and to get students to read more.

So, what can we do to increase the visibility and citability of our academic publications?

Below I offer tips and suggestions on what we could do before and after our research papers are published. They are based on my experience and that of many others whom I have met in my career.

Obviously, not all of them are useful for all of you. So do pick some that match your needs.

BEFORE PUBLICATION

TIP NO 1

Choose a popular topic within your field. Examples of popular topics in language education these days include, multiliteracy, multimodality, technology-enhanced language learning, critical thinking, intercultural competence, etc.

But how do we know which topics are popular? One simple way is to browse current issues of mainstream journals in our field. Look at articles published in the past 5 years to get an idea of the kinds of topics that are currently receiving research attention.

L2 writing research for example continues to be a popular topic. But one area within L2 writing that is particularly popular is written corrective feedback (Pelaez-Morales, 2017).

Hundreds of L2 writing researchers have examined this topic from various angles, but it appears that the number of new research studies will continue to flourish. Thus, research papers on corrective feedback tend to be more visible and citable.

TIP NO 2

Identify a lacuna or gap in your chosen topic and gain a first (or second) mover advantage. The advantage is clear: people will refer to our seminal paper for many years to come.

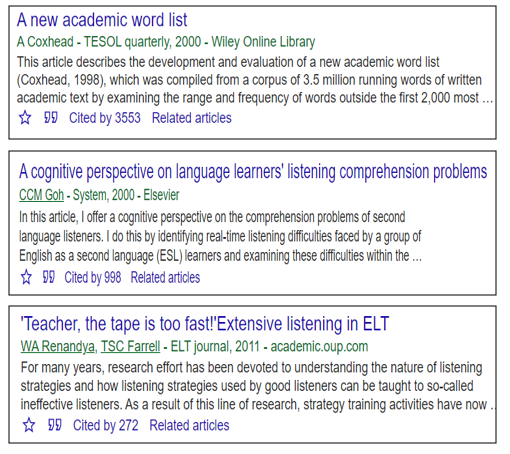

Examples of this include Averil Coxhead’s (2000) seminal study on the academic wordlist, which has generated some 3,500 citations, Christine Goh’s ground-breaking listening paper (2000), nearly 1,000 citations and my extensive listening paper (2011), 272 citations.

TIP NO 3

Publish in high impact journals. These journals are normally indexed by Scopus or SSCI, making them easily accessible to a large number of researchers from around the world.

Examples of high impact journals in language related fields include: ELT Journal (OUP), TESOL Quarterly (Wiley), Applied Linguistics (OUP), Language Teaching (CUP), RELC Journal (Sage), System (Elsevier) etc.

There are some high impact journals, which are not indexed in Scopus or other research databases such as Reading in a Foreign Language (RFL), published by the University of Hawaii. RFL is a highly regarded journal and widely read by L2 reading specialists.

TIP NO 4

Stick to the same topic and keep writing about it until we become known as a specialist in that topic. It normally takes about 10 years (or more) to establish ourselves as an expert in an area.

So if you’ve published papers on grammar instruction, stay with it and continue writing about it from different perspectives, e.g., Teaching grammar for young learners, Teachers’ beliefs about grammar instruction, Teaching grammar using the whole-part-whole approach, Features of spoken grammar in technology-mediated interactions, etc.

TIP NO 5

Write more and publish more. While the correlation between number of publications and number of citations is not perfect, people tend to read and cite work written by well-published scholars.

For early career researchers, the rule of thumb is to get at least one paper published annually. For mid-career researchers, the number can be as high as three to five per year. To achieve the goal of publishing one paper per year, you may need to have

- one in press paper (already accepted)

- one forthcoming paper (submitted and under review)

- one in prep paper (half-way through a draft paper)

- one paper idea that you’re planning to write

While it is good to publish in high impact journals, it is not always possible to do so. High impact journals have high rejection rates (so not easy to get in) and usually have a longer turnaround time.

If you are a junior faculty and still new in the publication game and you are keen to increase the quantity of your publication, you might consider publishing in good journals with lower rejection rates.

Click here for a list of good Scopus-indexed journals.

TIP NO 6

To further increase the quantity of publications, you may consider joint authorship. If you work alone, you may be able to publish one single authored paper a year. But if you co-write your paper, you and your co-authors may each have two published papers.

TIP NO 7

Invite a top scholar to be your co-author or co-editor. Co-authoring a paper or co-editing a book with a top scholar increases its visibility and the chance of being cited by other scholars.

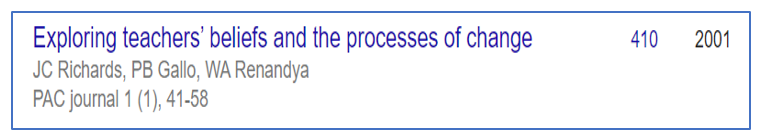

The paper below which was published in a rather obscure journal attracted 410 citations. Reason? Jack C Richards is one of the top scholars in ELT/TESOL.

TIP NO 8

Writing a book chapter is fine, although it tends to attract fewer citations than a journal article. Try to get your chapters published by top book publishers in our field such as Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, Wiley-Blackwell, Routledge, Springer etc.

TIP NO 9

Publish both research and conceptual papers. The former is usually read by researchers, while the latter may be read by both researchers and practitioners. Conceptual papers tend to attract a wider group of readers, which in turn may increase the visibility and citability of your paper.

One type of conceptual papers is a literature review article, often known as state-of-the-art article. State-of-the-art articles published in Language Teaching (CUP), for example, tend to attract a large number of citations.

TIP NO 10

Consider publishing a meta-analysis paper. A well-written meta-analysis paper tends to attract a higher number of citations, as the example below demonstrates.

My MA student has just completed a meta-analysis study on written corrective feedback and we are now working together to turn the dissertation into a journal article. I am confident that it too will attract a good number of citations after it has been published in a good journal.

TIP NO 11

Use a catchy title, one that will attract the attention of your target readers. Questions and controversial statements, for example, are common strategies writers use to attract readers’ attention.

The seminar paper by John Truscott below uses a very catchy title and immediately caught the attention of L2 writing scholars. Prior to the publication of this paper, people had generally accepted the collective wisdom that grammar correction improved student writing.

Two decades after Truscott’s paper was published, people still continue to engage in healthy debates about the effect of grammar correction on student writing.

Whenever you can, use shorter titles. Research by Letchford et al (2015) suggests that shorter titles tend to attract more citations and longer ones, other things being equal. One of the main reasons is that shorter titles are easier to understand.

TIP NO 12

Include a strong and controversial statement, where appropriate. In the paper above, Truscott famously says that ‘grammar correction is ineffective and harmful’. This strongly worded and contentious statement generated heated debates in the literature, resulting in his paper being frequently cited by writing scholars.

A colleague pointed out that there were many people who disagreed with Truscott and cited his paper for that reason. Does it not reflect poorly on the value of the citations (or quality of his paper)?

Not really!! First, Truscott’s paper has led to numerous and more rigorous research studies on grammar correction. We are now closer to understanding the role of grammar correction in improving student writing.

Second, disagreement is very common in scientific inquiry. One’s theory or hypothesis may be proven right or wrong.

Some 50 years ago, Eric Lenneberg (1967) theorized that language learning was not possible after puberty. The ability to develop native-like competence was biologically determined. Upon reaching puberty, the biological muscles responsible for language learning had already atrophied, he claimed.

Most people agreed with him back then. His 1967 paper received more than 12,000 citations. But we now know that his theory was only partially correct.

TIP NO 13

Write a strong abstract. The abstract is the first section of your paper that is read by an editor or reader. It helps them decide whether or not to read the rest of the paper.

Write your abstract clearly, highlighting the key points that you want to get across in the most efficient and appealing manner. For more tips for writing a compelling abstract: https://tinyurl.com/tdcl3xg

TIP NO 14

Use non-technical language as much as you can. While some technical terms cannot be avoided, keep this to a minimum. This is particular important if you want to reach out to a wider group of audience, including parents and teachers.

TIP NO 15

Use simpler language to explain difficult concepts. International best-selling novels are usually written within a more restricted range of vocabulary to make them more readable and accessible to their global readers (typically words that belong to the first 6,000 high frequency wordlists).

I too wrote this paper using simple and accessible language. A simple vocabulary profile analysis that I did on this paper using Lextutor showed that 96% of the words come from the first 3,000 wordlist. So this paper should be quite reader-friendly.

AFTER PUBLICATION

TIP NO 16

Share your work in a staff seminar. Invite your colleagues and graduate students to attend your talk. If you do this well, you will receive useful and honest feedback, which might inspire you to do a follow-up research study.

TIP NO 17

Present your published paper in a conference. You might want to do this a couple of times in different conferences, if possible.

Do make an extra effort to network with other conference participants, in particular those whose research interests are in the same areas as you. People who know you are more likely to read and cite your work.

TIP NO 18

Put your newly published paper in your email signature. I have seen lots of my NIE colleagues doing this to help make their publications more visible to their email contacts.

TIP NO 19

Upload your papers in Academia.edu, ResearchGate and other online repositories. Increasingly, researchers (especially those from low resource countries) turn to these online resources as their main source of references for their research. So putting your publications online seems like a sensible thing to do.

TIP NO 20

Promote your newly published papers in social media (e.g., FB, Instagram, Twitter etc). Do this several times as posts in social media tend to have a rather short screen time.

TIP NO 21

Cite your own published work. If you don’t cite your work, who will?

TIP NO 22

Include your published work in your course readings. You may also ask your professional colleagues to consider including your publications in their required or recommended course readings.

I sent my article “Extensive reading coursebooks in China” to Prof Richard Day who taught L2 Reading Pedagogy at the university of Hawaii and he delightedly included it in his course readings.

TIP NO 23

Be a member of large professional FB groups (e.g., Teacher Voices, IATEFL) and make your work known to the members. Teacher Voices, for example, has more than 11,000 members, many of whom are active language researchers.

TIP NO 24

Send your papers to your research groups, colleagues and other academic contacts. Make sure you provide a brief note explaining why you are sending the paper to them.

Highlight the potential benefits that your paper might bring to them, their colleagues and/or graduate students.

A former colleague, Dr Clarence Green, recently published an article on extensive reading. Following my advice, he sent out his in press article to his contacts, in particular to those who have published on extensive reading.

TIP NO 25

If you can, share your papers with top people in the field, too. Your papers will enjoy higher visibility if they are cited by big players.

If you have just published a paper on vocabulary for example, you might want to consider sharing it with top vocabulary scholars such as Paul Nation and Averill Coxhead.

If your paper is on extensive reading, you may want to send it to top ER scholars such as Richard Day, Beniko Mason, Sy-ying Lee, Stephen Krashen (and Willy Renandya, too).

CONCLUSION

Writing takes time; and getting your paper published in a good journal also takes quite a bit of time. Given the amount of time you have invested in writing and getting your work published, you naturally want your published work to be read and cited by as many people as possible. Your citation count is an indicator of the impact of your research on the field.

But as you already know, it takes even longer for a newly published paper to be cited. It may take one or two years before people stumble onto your paper and even then, they may not cite your paper.

Indeed, uncited research is not uncommon. It’s been estimated that some 25% of published research remains uncited (Noorden, 2017). The percentage is likely to be higher If you your paper is published in a less known journal.

The 25 tips I have shared in this paper may shorten the wait time, make your publications more visible and hopefully citable too.

There are many other citation tips that you may find useful. Simple but practical tips include choosing commonly used keywords in your field, using the same name (initial and surname) throughout your career and provide your researcher identifier e.g., ORCID if your surname is fairly common (e.g., Nguyen and Zhang).

As I mentioned earlier, not all of the tips are useful or relevant for you. But some of them are likely to help you disseminate your publications to a larger number of people, thus potentially increasing the visibility and citability of your published work.

REFERENCES

Nguyen, T.T.M., & Renandya, W.A. (In press). Growing our research impact. In C. Coombe, N. J., Anderson & L. Stephenson (Eds), Professionalizing Your English Language Teaching. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Noorden, R.V. (2017). The science that’s never been cited. Retrieved March 27, 2020 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-017-08404-0.

Pelaez-Morales, C. (2017). L2 writing scholarship in JSLW: An updated report of research published between 1992 and 2015. Journal of Second Language Writing, 38, 9-19.

Thanks so much pak Willy…it’s very very usefull..🙂👍👍

I can say that writing need a process of learning. Thanks for sharing pak Willy

What does Q1 journal mean?

emejing!

Thank you for the very useful tips Sir.

The tips are very practical based on the experience of the author as a productive researcher and a well-established teaching consultant.