“If reading and writing really were identical and not just similar, then…everything learned in one would automatically transfer to the other” (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000, p. 43).

For many years I have been trying to understand the link between reading and writing. I know they are related, but what is the nature of their relationship? Is it a reciprocal relationship, i.e., that reading affects writing in the same way that writing affects reading? Is one a pre-condition for the other to happen, i.e., does reading precede writing? Is reading a causal variable, i.e., does more reading results in improvement in writing?

WHAT DOES RESEARCH TELL US?

Years of research into the link between reading and writing tell us that

- reading is closely related to writing, so much so that some would say that they represent two sides of the same coin

- children learn how to read first and then to write (in that order, at least initially)

- if a child can’t read, they also can’t write

- good readers tend to be good writers, but not always

Research also tells us that

- reading and writing are not identical

- reading is ‘receptive’; writing is ‘productive’

- receptive knowledge does not automatically translate to productive knowledge

- L2 learners need to learn to transition smoothly from the reading mode to the writing mode

- even more advanced language users need to learn how to write more accurately, fluently and coherently. I have seen colleagues who are well-read but can’t write a coherent, well-structured abstract.

HOW TO BRIDGE THE GAP?

To answer this question, we need to make the best use of research findings and also insights from our experience working with diverse groups of students. We should also draw on our own experience as writers.

I outline below 5 key factors that need to be considered when we try to help students transition smoothly from reading to writing.

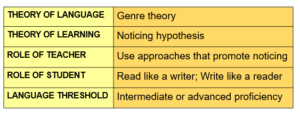

THEORY OF LANGUAGE

Genre theory seems to be the most suitable in my opinion. In a nutshell, it is a theory of language use that considers a piece of written text in terms of its purpose, audience, context and language features. The first three elements, i.e., purpose, audience and context, determine the way the text is organized and the grammatical and lexical features that are commonly used.

For example, a narrative text is typically organized around 5 elements, i.e., the characters, setting, plot, conflict and resolution, narrated in some chronological fashion. A story can be told in many different ways, but these typical elements are normally present. Typical language features we often see include the past tenses, time sequence markers, direct and indirect sentence structures, etc.

THEORY of LEARNING

One theory that is of particular relevance to our discussion is Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis (2010), which I summarize below:

- Input is important but not sufficient

- Learners need to notice the language features present in the input

- Noticing allows learners to turn input into intake, which after further processing gets incorporated into the acquired system

While most people agree that noticing is central to language learning, the theory does not provide detailed information about the amount and intensity of noticing, which is critically important to consider when we work with lower proficiency L2 learners.

Too much noticing can have adverse effects, resulting in L2 students experiencing information overload. For them, comprehending the contents alone is already quite challenging and take up a lot of their attentional resources. So doing both, comprehending and noticing, will only add to their learning burden.

ROLE OF THE TEACHER

Armed with a good understanding of the genre theory and noticing hypothesis, the teacher can use pedagogical approaches that promote active noticing. Those who have used the genre-based pedagogy are familiar with the standard procedures outlined below

- Building knowledge about the target text. This simply means explaining the social context and the purpose for which the text is written.

- Modelling and desconstructing the text. This refers to the teacher showing model texts and highlighting key language features.

- Scaffolding and joint construction. Here, additional guidance is provided before students write their own text.

It is the second step, modelling and deconstructing, that links with the noticing hypothesis. By drawing students’ attention to the way the text is organized and written, we are essentially telling the students to pause and think when they look at the model text so that they can make a conscious link between the what (contents) and the how (language).

When systematically done, there is a good chance that students may be able to express themselves in writing using the language features that they have attended to during classroom instruction.

THE ROLE OF THE STUDENT

What students have learned in class is likely to be partial or incomplete, so they need to continue their learning beyond the classroom. They can do their independent practice of noticing language features when they read texts. This requires some getting used to, because most people naturally pay attention to the contents of what they read, not the way the text is written.

However, if students are truly interested in improving on their writing, they will need to consciously and systematically attend to both the contents and the language. They can do this by doing the following:

- First, read a text like a reader. Students should first read a text for meaning, focusing on key ideas and important details. They can do this one or twice, depending on the text they are reading. Reading an academic text for example often requires several readings.

- Second, read it like a writer. This is where students need to apply the ‘pause and think’ technique I mentioned earlier. When reading an abstract for example, they should pay attention to its overall structure. The first sentence often provides the context of the study, the second sentence is about the purpose of the study which is then followed by the research methodology (i.e., participants, instruments, procedures), then results and implications. They should also notice the words, sentence structures, the tenses and other relevant language features.

Students will soon find that abstracts tend to be written in a rather formulaic manner. They will start noticing and remembering common phrases and expressions that writers use to craft their abstract. In time, they will be able to use these in their own writing.

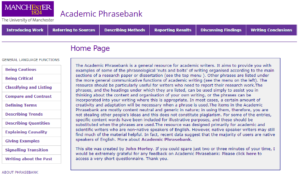

If they need further help, there is a very useful website that compiles hundreds of formulaic phrases and sentences found in academic writing.

When introducing the importance of your research topic and inadequacy of past research, authors often use the following (Source: Manchester Academic Phrasebank)

Importance of your research topic

A key aspect of X is …

X is of interest because …

X is a classic problem in …

A primary concern of X is …

X is an important aspect of …

X is at the heart of our understanding of

Inadequacy of past research

Previous studies of X have not dealt with …

Researchers have not treated X in detail.

Most studies have only focused on …

Such approaches have not addressed …

Past studies are limited to local surveys…

Most studies failed to specify whether …

LANGUAGE THRESHOLD

The ideas I outlined above are generally applicable to students of different proficiency levels. Regardless of their proficiency levels, they can benefit from a systematic switch from a meaning-focused to form-focused mode of language learning; from a semantic to a more syntactic mode of processing.

However, for academic writing, which is linguistically and cognitively more challenging than other types of writing, a certain level of proficiency may be needed. Higher proficiency students (B2 or C1) would benefit more from the noticing ideas discussed here.

The reason is simple. These students have already had sufficient academic and linguistic background knowledge. What they need to do is to set aside their spare attentional resources to attend to important language features that writers use in the different sections of their academic papers.

FINAL THOUGHTS

You may have bridged the gap that separates reading and writing, but that’s just the beginning of your writing journey. If you want to sharpen your writing skills, you will need to follow the advice of accomplished writers. Most if not all of these writers follow the footstep of the Ernest Hemingway. In an interview with George Plimton, Hemingway said: “I write every morning”.

You too can (and should) write every morning. Perhaps not 3 or 4 hours every morning, but 1 hour at least. If you do this regularly over 6 – 12 months, your writing skills will improve a great deal: your ideas and words flow more smoothly and your text becomes more linguistically and logically coherent. Plus you get the enjoy numerous other benefits of writing (click on the image below).

REFERENCES

To download the ebook version of this article, click on the image below.

Your topic is very inspiring me a lot. I know the relationship and I want to apply it for my class. Thanks for sharing the ebook pak Willy.

This is refreshing. Well-designed tasks help learning take place effectively especially in aspects of modelling and scaffolding. Thanks